1700s

CREDIT: Ivan Bunn and David Butcher

Origins

This article is in its original form, with minor alterations. It was published (with editorial adjustments and changes) in English Ceramic Circle Transactions, vol. 21 (2010), forming pp. 49-74 of that journal.

Added: 20 July, 2024

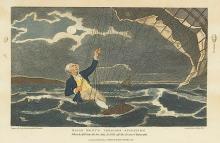

Saved by the Argus

One of the earliest balloon flights in England took place on Saturday, 23 July 1785, at 4.25 p.m. in Quantrell’s Gardens, Norwich – located in the city adjacent to present-day Queen’s Road (part of the A147) in the area now occupied by a large Sainsbury supermarket. The chief organiser and sponsor of the event was Major John Money (1724-1817), a local man who lived at Crown Point, Trowse, and was an officer in the 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot. He had something of a penchant for acts of daring and this particular episode was no exception.

Added: 22 October, 2025

On 15 January 1737 – the year being 1736, by use of the old Julian Calendar – King George II (1683-1760) made a sudden and unplanned landing at Lowestoft, on a return journey from the North-western German province of Hanover – where he and his father, George I, were the rulers (as Electors) as well as being monarchs of Great Britain. Both of them made summer journeys, periodically, to spend time in their land of origin, and it was on his return from one of these that George II was forced to put ashore.

Added: 20 October, 2025

Inns

The configuration of roads and the importance of land transport have always been major influences on the development of towns and their inns. Large yards were necessary for stabling horses, and for standing carts and carriages; buildings were required for storing hay and other forage; and provision had to be made for watering the animals. Adequate accommodation was also needed for those people making overnight stops or staying in a place for longer.

Added: 18 October, 2025

A small house (early 18th century)

John Cousens (carter) lived with his wife Mary in a three-roomed house somewhere in the side-street area to the west side of the High Street. Their son, Benjamin (aged twenty-four years) had left home, but their daughter, Mary (aged twenty years) was possibly still living there. When the inventory of Cousens’s goods was made on 6 June 1711, his total estate was valued at £73 8s 9d. Out of this sum, £50 consisted of good debts and a further £16 17s 0d. of his working equipment and horses.

Added: 5 October, 2025

(16th-18th Century)

Construction details

In May 1545, the Duke of Norfolk was carrying out a review of coastal defences between Great Yarmouth and Orford because of a perceived invasion threat from France. Having commented on the hostile landing capacity of both anchorage and beach at Lowestoft, as well as on the positioning of the three small gun batteries, he made the following remark concerning the place itself: “The town is as pretty a town as I know any few on the sea coasts, and as thrifty and honest people in the same, and right well builded.” – ref.

Added: 24 September, 2025

In some ways, buildings are every bit as much historical documents as written sources and can inform the observer of many aspects of human activity in days gone by. Where they have survived in original form, they have much to say of former economic and social conditions – be they domestic, ecclesiastical or industrial in nature. And, if altered and converted at different times, there is just as much to be learned from them. Let us take three of Lowestoft’s buildings, covering these three categories, and consider each one of them in turn within its context.

Added: 18 September, 2025

The foundation called the Good Cross Chapel is a lesser-known part of Lowestoft’s religious history, which once stood in the extreme south-eastern corner of the parish near the junction of the present-day Suffolk Road with Battery Green Road – possibly in the location of what is now the Fish Market entrance.

Added: 15 September, 2025

Mid-Late 18th Century Urban Status and Identity

The field of study constituting urban history is both complex and wide-ranging, combining a variety of sources and a number of disciplines. Economic and social history may unite in helping to explain and illuminate a community’s existence and function, but integration with historical geography and demographic features is required in order to produce a deeper understanding of the human activity which created that entity.

Added: 12 September, 2025

The type of agriculture practised in Lowestoft during the Early Modern era was of mixed variety, as was the case with most other communities in lowland England. And it was not only mixed in combining crops and livestock; it was also mixed in the sense that many of the people who farmed the land had other interests. It is unfortunate that the two key documents which reveal so much about conduct of agriculture in the parish stand in isolation from each other.

Added: 6 September, 2025